The present-day Commonwealth of Niflungland is politically descendant from the Margrave of Nibelung, created from a merger of lands held by the Wettin family and the Margrave of Meißen in the 1060s. The earliest existence of the Nibelung family itself can be traced to 1035, when the first recorded mention of the family that would eventually adopt the form Niflung is found. Since then, it has gone through several periods of reform and change, and has been a major party to happenings in Central Europa from the 12th century to the recent collapse of Europa after the Great War of 1914-1918.

The High Middle Ages[]

The history of Niflungland begins in the 11th century AD, with the emergence of the House of Nibelung as a major political force in the Holy Roman Empire. The origins of the family itself is disputed by contemporary scholars, but in the 1035, the first recording of the family as contenders for the throne of Denmark after the death of Canute the Great, their origin was said to be from the very same Burgundian family for whom the famed Nibelungenlied was named. This is now, of course, considered largely to be legend, and the more likely origin is as Danish vassals to Canute who had the fortune of marrying away both daughters and sons to a number of important families due to the tremendous wealth that they suddenly acquired in the early 11th century, wealth that they used to assist Conrad of Speyer as King of the Romans in 1024. An advantageous marriage to the House of Wettin in 1078 was followed ten years later with the acquisition of the Margrave of Meißen, from which this branch of the House of Nibelung would build themselves to be Prince-Electors of Saxony. The other branch of the House of Nibelung did not emerge as a presence in the 12th century in the former Nordmark, what would become Brandenburg. The family would become famous for intrigue against former friends and allies; unlike the Wettin-Nibelung branch, the Brandenburg-Nibelung branch of the family became very close to the court of the Emperor. When the Wittelsbach family was cast from the Electorate of Brandenburg in 1361, the Brandenburg-Nibelungs made especial efforts to cultivate relations with the Emperor, Charles IV, and later his son Wenceslaus. They established a marriage contract with Wenceslaus' brother, Sigismund, later Holy Roman Emperor, and as a result Sigismund's brother-in-law, Klemens, was awarded the Margrave of Brandenburg in 1410 upon the former becoming King of the Romans.

The two branches of the family grew separately and participated in the conflicts of the coming centuries with different levels of involvement. Despite their closeness to the Emperor Sigismund, it was not they but the Wettin-Nibelungs of Saxony who came to the Emperor's aid in suppressing the Hussite Wars of the 1420s and '30s. They would be rewarded with further lands for this, bringing them closer to the political power they held by the 1500s. In 1467, the two branches merged with the marriage of Anne von Brandenburg-Nibelung to Duke Heinrich August von Nibelung, whose sons Friedrich and Johann would become Prince-Electors of Saxony and Brandenburg, respectively, during one of the most trying periods of all Niflungan history.

The Reformationzeit and the German Princes[]

Maximillian II, Holy Roman Emperor, gave his blessing to the Electorate of Nibelungen in 1571

The history of the German Reformation is certainly not an event which requires full recounting; the House of Wettin-Nibelung gave rise to Friedrich the Wise, responsible for protecting Martin Luther and his brothers and nephews in the Ernestine line. These were brought to a swift close with the defeat of a united Saxony against the steadfastly Roman Catholic Brandenburg-Nibelungs in the Schmalkaldic war of 1546-47. The Brandenburg-Nibelungs soon saw their line under Moritz von Nibelung elevated to the Elector of Saxony while his brother, Joachim, ruled Brandenburg as Elector. The two electorates would be merged by this dynastic union when Joachim died in 1552 of fever he had caught during his expedition into Pomerania. His son, Jörgen took the Electorate, but the Duchy itself passed to Moritz until his death, without issue, in 1571. The two Duchies were joined under Jörgen that year, into the Electorate of Nibelungen at the grant of Emperor Maximillian II, who was guaranteed by the merger the vote for his son Rudolf. This followed dealings with Jörgen while he was Elector of Brandenburg with James V of Scotland for the hand of his daughter, Mary. Seeing opportunity for the Nibelung family, Joachim, Jörgen's father, convinced his brother Moritz to assist with the brief war between James and his uncle Henry VIII, who was intent on making Scotland a Protestant territory. He sent 2,000 men to Scotland to assist the successful rout of the paltry force sent by Henry VIII at the battle of The Scottish force under the leadership of Robert, Lord Maxwell, commenced movement into England after the defeat of the English forces, continuing the series of battles that would come to a close in 1575. James signed with Joachim a treaty of marriage that would make Jörgen, or George, High Steward of Scotland with marriage to Mary, and his son, Huldrych, King of Scots.

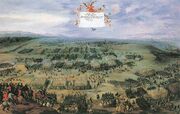

In Germany, the early half of the 17th century was dominated by the Thirty Years War, which saw the Holy Roman Empire descend into chaos. Huldrych initially took neither side in the conflict, hoping it would pass him and his duchy by. He was, however, given no choice in the

The Thirty Years' War dominated most of the seventeenth century.

matter by Gustav Adolf of Sweden, when the latter invaded and forced war with Nibelungen. Much to the dismay of the Catholic forces who had so readily welcomed the rule of Jörgen as a Catholic force, Huldrych had grown up in Scotland during the age of John Knox and the rise of Presbyterianism. Upon his father's death in 1595, he returned to Germany and declared himself a confirmed Calvinist. He nevertheless remained neutral, hoping that the conflict would pass him by without stirring his Lutheran subjects against his Calvinism. When, in 1530, Gustav II Adolf, invaded the German lands, he forced the alignment of Nibelung with him. Upon their king's death in 1632, the Swedes continued their war but saw sound defeats after Huldrych decided against his forced alliance with the Swedes and aligned himself with the Catholic League. The war continued well into the mid-17th century, closing for the Nibelungens in 1653 with the Treaty of Stettin after an expedition of Nibelungen forces into Swedish land, and a crushing defeat of the Swedes at Öland.

That same year saw the establishment of Cromwell as Lord Protector of England, who had overthrown Huldrych's cousin, Charles I, descent from James V's brother, Arthur Stewart, Duke of Rothesay, whose father James had inherited the throne of England in defiance of Huldrych's claim to the throne, which was give to him in exchange for his promise of assistance in conflict with the House of Pomerania. Huldrych tried to assist his cousin but the kangaroo court erected to kill Charles completed and committed the regicide before a war could be waged. By late 1653, Huldrych had fallen gravely ill, and died the following year. His son, Huldrych, often known as Ulrich II, took the throne as a 16-year-old boy. He was, however, as resolute as his father in his German Calvinism, staunchly opposed to the radical puritans under Cromwell and politically aligned with the Catholic League. He held court in Scotland more than Potsdam, and established a strong armed force on the border with England, to oppose the armed incursion by Cromwell that had begun with a Phyrric Cromwellian victory at the Battle of Dunbar in 1650. Cromwell knew better than to go to full-scale war with a force allied with both the French and the Papacy. He instead concentrated his efforts domestically until his death in 1658. Ulrich II was sternly opposed to Cromwell, but he did admire the structure of the New Model Army, and was swift to begin adopting its style in his own armies, something that helped him when he established forces on the border of England to invade if the Restoration of Charles II was not accepted by the English Parliament following the resignation of Richard Cromwell as Lord Protector.

The Rise of the Kingdom[]

The eighteenth century saw expansion in the Niflungan German lands, where the Thirty Years War had emptied the state treasury. In 1688, Ulrich II's son Ulrich III inherited the throne of Niflunga. His reign was marked with efforts to rebuilt the treasury as well as convincing the Emperor, Leopold I, to recognise Niflunga as a Kingdom. He accomplished this through an alliance against former allies the French in the War of Spanish Succession. His argument was that, in spite of the German law banning any Kingdom in the Holy Roman Empire except Bohemia, the core of Niflunga was in fact the Kingdom of Scotland, since it was ranked higher than any other state under the reign of the House of Nibelung. Through the alliance with Leopold I, the growth of Niflungan power began a new phase. The alliance with Austrian power was maintained until the War of Austrian Succession during the reign of Ulrich III's son, Jörg I. Once again poised against England in conflict, Jörg shifted his alliances again by invading Austrian-held Silesia from Saxony; while he led his forces to battle in Silesia, his chief general in Scotland, James Francis Edward, whom was the Niflung and French recognised King of England, led the invasion force into England from Scotland. Despite being a Catholic, James enjoyed some popularity in Scotland among both the Presbyterians and Highlanders. As appointed Steward of the Throne in the absence of Jörg (George I of Scotland), he was in charge of the raising of armies there. The war against England was not as successful as the King's ventures into Silesia, which gained a large portion of the province for him from his rival Maria Theresa in Austria.

Niflungan troops advance at the Battle of Hohenfriedberg, a small victory secured with Prussian aid during the War of Austrian Succession.

The successful campaigns against Austria would continue for the duration of Jörg's reign, along with a close alliance with the Hohenzollerns, cousins of the Nibelung family that had been installed in the Duchy of Prussia, and had, with Niflungan assistance, successfully Germanised much of the land there. They had formed a close relationship with the Russians, and had, along with the Niflungans, entered a pact to partition the Polish lands in 1762, the first of three partitions, the last of which would spell the end of Poland as an independent entity, though under new leadership and a new name for their nation, the Polish people have once again united under a common banner. While the Hohenzollern's under Friedrich II and then his nephew Friedrich Wilhelm III partitioned the rest of Poland with Russia and Austria, Niflunga turned inward. Jörg I would die in January 1773 and his son, Jörg II came to the throne in a very decisive moment for Niflunga. The English colonies in the Americas were quickly becoming hotbeds of political unrest, offering a stunning opportunity for Niflunga to take advantage of her old rival in a time of trouble. Several Scottish spies were sent to the colonies of Massachusetts Bay, New York, Virginia, and Pennsylvania to investigate the situation there. One spy arrived in the small city of Boston in the first week of December, and almost immediately reported a rather childish and amusing but nevertheless meaningful gesture on the part of the colonists, who on December 16 raided a number of trading ships in the harbour and cast their cargo (mostly of tea) into the bay in protest of English taxation laws. Over the next few years, a number of developments convinced Jörg II in his capacity as George II of Scotland to commit funding to the American expedition and sent a cohort of Scottish troops and several German military advisers to the American forces under George Washington in the late 1770s. He soon learned that his allies the French had made similar commitment of funds, but as yet had not committed troops. In a trip to renew the Auld Alliance between the Scots and French in 1777, the Niflungan delegation, in conjunction with some Americans who were present, convinced France to commit troops and recognise the young Republic, and in formal declaration in June of 1778 officially recognising the United States of America by the Kingdom of France and Niflunga, which led to armed conflicts between English and Niflungan forces in Scotland in the early 1780s, finally negotiating a peace with the Treaty of Paris of 1783, which granted Niflunga a short-lived colony in what would become Maine, and official recognition of the United States by England.

The French Wars[]

Following the French Revolution of 1789, relations between Niflunga and the French soured, leading Niflunga to sign a Treaty of Alliance with England in war against the French throughout the 1790s. In this time, relations with the Americans were further improved with the exchange of 25 million gulden for the purchase of the distant and impractical Maine colony, followed by a Treaty of Alliance that saw the first American soldiers in Europe, sent to Brandenburg-Saxony for military training in the élite Niflungan military academies in Potsdam, Dresden, Stralsund, and Frankfurt-am-Oder, which offered English-language courses and training led by Scots who taught there. Some of these Americans remained in Niflunga, learned German and joined the Amerikanische Zenturien, or “American Centuries”, 100-man miniature armies attached to the Niflungan Army and Navy. So plentiful were the Americans that they became a phenomenon in Saxony, of which one relic remains: the city of Washington, just a few kilometres from Dresden on the Elbe River, is still today an exclusively English-speaking community descent from Americans who moved to Niflunga and stayed.

In the period following the rise of the French Republic, Jörg II did all he could to resist the French armies moving through Germany, and sent forces across the western lands to meet advancing French armies and assist the Austrians, which was largely accomplished, securing Austrian victory Valmy in 1792. After the regicide of Louis XVI by the French rabble, England joined Austria, Russia, Niflunga, Prussia, and several others in forming a European Coalition to crush the rebellion of the French and restore the rightful rulers of the Kingdom of France. The forces won crushing victory after crushing victory for most of the 1790s, until the emergence of a strong French general from Corsica named Napoleon Bonaparte, whose successful invasion of Italy came as a great surprise and a massive blow to Archduke Karl of Austria. Niflunga countered with a major attack at the heart of France herself, laying Paris to siege in 1796 for several months. After the mass-murder of the Vendéens in 1795 and 1796, official orders of “no quarter” had been issued to the Niflungan troops if the city were taken; revenge for the death of the King and the mass-murder of Royalists would be the decimation of Paris herself. It did not, however, come to this, and the siege was lifted with the coming of winter in 1796, but withdrawing Niflungan troops could not be stopped from acts of violence against Frenchmen they encountered as they withdrew to Belgium, killing several thousand and burning every Republican village they encountered to the ground. The black flag was carried before Niflungan troops for the duration of their wars against the French, and created a violent animosity which survived as long as the now collapsed French Republic. With the restoration of the Capetian House, relations have started to repair themselves.

The New Dynasties[]

Great troubles awaited the Niflungan forces with the turn of the 19th century, as Jörg II died without issue in 1800. While great arguments and debates ensued over his successor, Niflunga was forced to drop out of the Second Coalition, formed only a year before. They signed a peace with Napoleon that turned over short-lived conquests in Belgium to France. Meanwhile, long-harboured resentment of Niflungan rule came to a head in Öland, where a popular revolt rose to overthrow the Kingdom of Niflunga's power and establish an

After the collapse of the Niflung dynasty, a replacement was found among the relations of Mary Stuart, daughter of James V of Scotland.

independent state. This sped the decision of the new King significantly, and the joint parliaments of Berlin and Edinburgh, meeting together in the City of Wittenberg in August of 1801, appointed a Scotsman, a descendant of James V of Scotland and therefore cousin of the Nibelungen line through Mary Stuart. King Robert I (Robert VI of Scotland), as the young James Robert Stewart styled himself, marked the beginning of a new era of Scottish rather than German rule of Niflunga.

One of the last acts of Jörg II before his death was his conversion, and the conversion of a large segment of the population, to the pre-Christian faith of the ancient Nibelungs, a faith to which they still clung when the House emerged in the 1030s. Meanwhile, the Highlanders seemed more open to the idea of a native faith, and in the Shetland Islands, Hebrides, and Orkey Islands an emergence of a Pictish religion began. The new King Robert was a lowlander, and hardly of this inclination; nor was he especially interested in seeing the re-emergence of the old religion, something already embraced almost in full by the Reichstag in the German territories, and with especial zeal by the rebels in his Swedish holdings. As an effort to curtail the movement without opening a new religious war in Niflunga, he founded the United Church of Niflunga (Vereinigte Kirche Nibelungen), which brought together all Lutheran, Calvinist, Presbyterian, and Pietist congregations for discussions in 1802. After a great deal of debate and argument, a central church body was formed to govern Christianity in Niflunga, though individual congregations retained autonomy in confession and liturgy, so long as it fell into a jointly reviewed Lutheran and Calvinist Rubric, the former being referred to as the “German Rite”, the latter as the “Scottish Rite”. Roman Catholics, many of whom were the Highlanders who were converting to outright paganism, declined sharply in population. By 1810, they were a paltry .06% of the entire population. The United Church of Niflunga was met with the rise of Jörg's small circle of aristocrats who practised the Old Ways, dubbed the Hochorden der Wotanssöhne (“High Order of the Sons of Odin”) by Jörg and his associates. The Hochorden was quick to reform itself to be a suitable national force to meet the VKN, and in 1804 officially styled itself the Orden der Ritter des Wotansauge (“Order of the Knights of Othin's Eye”). The ORW, as it was popularly known, surged in membership as the only central authority on pagan practise in all of Niflunga. Through efforts largely in spite of the King, the ORW successfully brought the pagans in Öland back under Niflungan governance by convincing them to all become part of the ORW. Reluctantly, the leaders of the rebellion recognised Robert I as King of Niflunga and, as such, Duke of Öland.

Robert went to war with the French in 1805, but was ill-prepared to meet them in battle and saw the first major defeat of Niflungan troops on the continent since the Thirty Years War at Jena in 1806. In November, Napoleon sat at Berlin and issued the Berlin Decrees, establishing his abortive Continental System which forbade the importation of British goods to the continent. This was, of course, something he could not enforce on Niflunga, whose Scottish territories shared a border with Britain, and throughout the duration of the Napoleonic era, Scotsmen became increasingly wealthy through the business of smuggling British goods into Europe by way of Scotland, making the continental system utterly pointless in Europe, but crippling to the French economy. Meanwhile, England prepared with her allies in Austria, Prussia, and Russia to form a new coalition against the French. The next two major Coalition Wars, between 1806 and 1809, Niflunga would remain neutral at the behest of Napoleon, who was in the position to dictate terms to Robert and his son Malcolm V of Scotland (Malcolm I of Niflunga). Robert, already an old man upon his accession, died in 1807 and his 23-year-old son Malcolm took the throne. Malcolm was as steadfast as his father in his Christianity, but he was far more open to German culture and custom, despite his thoroughly Scottish name. He took it upon himself to learn French, Norse, and German in addition to his native Scots; this soon had him dubbed “the People's King”, a name he relished. After Napoleon's expedition into Russia he gained even more popularity by joining the Sixth Coalition against Napoleon, which met the French leader outside of Leipzig in 1813 and saw decisive victory.

The Fall of Napoleon and the Vormärz[]

After the defeat of Napoleon, Malcolm took a leading role in the move toward nationalisation that Napoleon had begun in France. He did not care for the Napoleonic code of law, but favoured something similar to what had been done in Scotland since the 13th century; a royal parliament which held strongly to the English Common Law, subordinate to but still able to resist a King. He attempted to transplant the Scottish form into the German lands with some success during the rule of Napoleon over much of Europe, but found increasing resistance to the structure after 1813. The world was distracted for a moment in 1815, when Napoleon escaped his prison in Elbe and attempted to bring France under his rule again. At Waterloo, Niflungan forces joined with English forces under Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington and then joined with Prussian and Bavarian forces to drive Napoleon to rout at the same battle under General Gebhard Blücher. King Malcolm was not present but remained on the continent during the battle, in Potsdam at a palace gifted to his father by Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia.

Following Waterloo, France returned to the reign of the Bourbons for a time, and then shattered into several warring states, the first of the Flemish in the north, the Bretons to the northwest, a united Basque nation to the south-west, Italians and Swiss annexations to the southeast, and the only defined “French” nation centred in Paris and under rule of worker's communes. The violence that followed would endure into the next century. While France was at war with herself, the people of Germany were driving for more unity. Under the Austrians' guidance, a German League was formed, styled after Napoleon's Confederation of the Rhine, but incorporating far more. Due to good relations with the Belgians, Niflunga was able to convince the Flems to join as well as the Dutch in a re-made Holy Roman Empire, to replace the ancient structure finally shattered by the French in 1806. The German League was modeled after the Holy Roman Empire in that all the nobles and leaders of the various principalities, duchies, kingdoms, and free cities, met at a Diet regularly to discuss the state of the German nation. The difference was that in addition to this Diet, there was a standing assembly of representatives of the various states held in Nuremberg, which was itself removed from the rule of the Bavarians and made a free city at the suggestion of King Malcolm, observing a similar structure in the United States. This structure stretched from the eastern-most border of Prussia to the western-most border with the Flems, to the southern-most border with the Adriatic and the Swiss Confederation, whom could not be prevailed upon to participate.

The Frankfurt Reichstag in the Paulskirche, Frankfurt-am-Main, was just one of many disruptions to the Niflungan-supported German Confederation in 1848.

There was then a period of peace in Europe, with the exception of colonial wars waged by the British against her old rivals in Spain, who was making incursions into Africa now. Niflunga stayed out of the colonial race, now more interested in domestic affairs. In Germany, new thoughts were stirring; a Prussian Jew named Karl Marx published his Manifesto of the Communist Party, co-written with Friedrich Engels in 1848, and almost immediately thereafter, Germany erupted into flame, along with much of the rest of Europe. The overthrow of the Bourbons and the descent of France into factional chaos was a precursor, occurring in 1830. In 1848, German rabble-rousers, shouting slogans both from Marx's work as well as various carry-overs from the French toppling of Charles X eighteen years before, driving against the rule of the German princes in the German League. A group created their own Reichstag in Frankfurt-am-Main, to rival the de jure body in Nuremberg; they were recognised by violent upheavals in several major cities, including Dresden and Berlin. The former went as far as to declare Saxony a free state, subject to the rule of the Frankfurt parliament with its own government independent from Niflunga. One of Niflunga's most famous artists and musicians, Richard Wagner, took active part in the revolution and the government; he fled, along with the other rebels, to Switzerland when news of the Niflungan army intervening reached Dresden. Those who remained behind were taken to Berlin, where they were hanged according to the Scottish method instead of being shot or beheaded, as was the German style. Malcolm's early experiments with learning German culture and working closely with the Germans were long over; he was now enforcing Scottish law on the German people, and creating division within his own Kingdom as a result.

The Unification[]

The 1848 revolution was successful, however, in causing the collapse of the Nuremberg Reichstag. All the principalities of Germany turned against the notion of a unifying Reichstag and the Duke of Hesse personally quelled the body in Frankfurt. Nuremberg was thereafter re-annexed to Bavaria, an act which all German princes, as participants in the German league, were obligated to oppose. Malcolm, however, was alone in his opposition; seeing no diplomatic support for his opposition, he moved to outright war against the Bavarians. Austria, which was at the time tied closely with both kingdoms, was kept out of the war by constant appeals by each to support them. The Bavarians were successful, however, in recruiting Baden, Württemberg, and Hesse to their aid, while Niflunga gained alliance from the Prussians, Dutch, and Flems. Hanover, allied with England and consumed by her own affairs, opted out of the conflict, and various small states likewise joined with Hanover as the Unangeschloßte Verein or “non-aligned federation”. With pressure put on the Bavarians on their western borders by the Dutch and Flemish armies, Niflungan troops with their Prussian allies moved from the East into Bavaria, marching as far south as Regensburg, defeating the Bavarian army at the Battle of Hemau in April 1850. The Peace Treaty negotiated with Bavaria following this shattering of their forces allowed them to keep Nuremberg should the northeast of Bavaria, only recently gained by the Bavarians, be ceded to Niflunga. Negotiations continued almost until September, while the Dutch and Flems kept fighting Baden with great success in the West. Finally, an agreement ceding the towns of Bayreuth, Hof, Kronach, and several others to Niflunga, and Nuremberg becoming part of the Kingdom of Bavaria. Flanders and the United Netherlands were awarded portions of Bavarian holdings in the Palatinate, which had been overrun by the end of the year.

Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I was proclaimed Emperor of Germany in 1871 after his armies defeated an allied force of Prussia, Niflunga, Flanders, and the Netherlands.

In December of 1850, Malcolm, now in his 66th year, caught a chill and died. The only heir to the house was his nephew, only 10 years old. Therefore, the Lord Protector, John Moray, Duke of Rothesay, took command of the government. He spent the next eight years doing very little aside from conspiring against the royal house, succeeding in 1857 of having Robert II of Niflunga declared a bastard, and himself taking the throne on the legal basis of the old tradition of the official heir being granted the Dukedom of Rothesay. Johann I of Niflunga (John II of Scotland) took the throne officially in 1858, ending the short-lived Stewart Dynasty of Niflunga and beginning the Moray dynasty. Moray had in the meanwhile arranged for himself a marriage with a Hanoverian princess, Charlotte of Clarence, who had by 1858 bore him a daughter and a son. He had since moved entirely from Scotland to Germany, seeing the divisions created by Malcolm during the last years of his reign. His son was introduced to the ORW, who gained an increased presence in the government under the appeasing Johann. The next few years were dominated by the rise of political sentiment once again for a united Germany; a Niflungan whose family had left Brandenburg for Austria shortly after the defeat of Napoleon, Otto von Bismarck, took the role of Chancellor of Austria in 1862, a year that marked the high point in Niflungan-Austrian relations. Bismarck had succeeded in quelling internal opposition to Austrian rule by the late 1860s and pulled together a coalition he called the Süddeutscher Bund, to face the rising power of the Hannoverian Unangeschloßte Verein. A series of intrigues that led to Austrian annexation of the Danish Schleswig-Holstein province as well as much of Thuringia by 1868 put the Austrian party and the Süddeutscher Bund at the head of German affairs. The heavily Catholic Austria had very little patiences for Protestants, and much less for other religions, saw relations quickly sour between Bismarck's Austria and Niflunga. In 1870, Austria declared all non-Catholics under taxation and declared that the only recognised faith would be the Catholic faith, a measure implemented throughout the Süddeutscher Bund. Shortly thereafter, Niflungan spies intercepted messages from Austrian agents in Denmark hinting and plans for a war with Niflunga. Johann I read the documents aloud before both the Parliament in Scotland and the Reichstag in Berlin, and Niflunga declared war on Austria the next day.

The German Empire as declared in 1871 in Nuremberg, ruled by Franz Josef I, including Niflungan Scottish and Swedish holdings

War with Austria turned from Niflunga's greatest victory into one of her most crushing defeats after her initial allies in Hanover abandoned her. The Prussian forces took and held much of Austrian Galatia, which weakened the blow somewhat, but the end result was a terrible defeat for Niflunga and her allies. Austria gained the province of Alsace-Lorraine from the Flems, who had recently conquered it from the Parisian commune, while half of Niflunga's Franconian holdings had to be ceded back to Bavaria. The Treaty of Nuremberg of 1871 also saw the proclamation of a German Empire answerable to Vienna, of which Prussia and Niflunga were made a part, as well as Holland, Luxemburg, and the newly won Danish provinces. Though the individual states kept much autonomy, the official borders of the Austrian Empire now stretched from almost the end of the Danube river to the North Sea, an empire the likes of which had not been seen since the 16th century. Franz Josef of Austria was crowned Franz Josef, Emperor of Germany on 18 January 1871. Bismarck's cunning also convinced the Emperor and the rest of the cabinet to convert the various subdivisions of the former Austrian Empire into autonomous states similar to those in Germany. The Kingdoms of Hungary, Bohemia, and the Grand Duchies of Moravia and Croatia were officially recognised as part of the Greater Empire in the following years, as Bismarck tore apart Austria's old system in favour of a new, streamlined structure.

Fin de siècle[]

With the closing of the 19th century, the creation of a united and powerful central Europe had been realised, with holdings throughout what would become known geographically as Nordland. Johann was far from well-pleased with the notion of a united German state, since it weakened his own position in the region and of his alliances. He was, however, sympathetic to the democratic cause of the Frankfurt Reichstag, and began moving his own kingdom in that direction. His first action toward this end was the devolution of power to the German Reichstag, Scottish Parliament, and Ölander Althing. Upon his death in 1873, his son, Johann II of Niflunga, continued this movement toward more liberal government in Niflunga. Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, movements were made toward the final drafting of a Niflungan Constitution, which was finally issued in 1888 by a joint meeting of members of the Reichstag, Parliament, and Althing in Johann's chosen capital of Edinburgh, the first time an official capital of Niflunga had been named. This stirred a great deal of resentment from German and Swedish nationalists who favoured Berlin or Dresden as the capital, resentment which would continue to grow as the world moved toward war.

Otto von Bismarck died in 1898, leaving the highly conservative Franz Josef I in control of an Empire which sprawled the European continent from quite nearly the delta of the Danube River in the East to Niflunga's Scottish holdings in the West. For the first time since Charles V, the Habsburgs ruled over an Empire upon which the sun never set. Niflunga played a crucial part in the structure of this empire, with Niflungan representatives leading the movement toward a liberal structure resembling the Frankfurt German Federation of 1848. Franz Josef, even more than Bismarck, was heavily resistant to such ideas, which brought Johann II and Franz Josef I into heated conflict. Several princes in the north, formerly of Hanover's Unangeschloßte Verein, joined Niflunga in a push against the conservatism of the Emperor. Johann knew historically what brought the strongest sense of offence to the Austrians: religious unrest.

Niflunga's population in the German lands had long been moving toward the teachings of the ORW, and in Öland the last Lutheran church closed

Upon being honoured with government sponsorship under Johann I, the ORW adopted a new emblem, comprised of the Elder Futhark surrounding a triangle, symbolising the three roots of Yggdrasil, whence Othin gained wisdom, the eye of the Alfather Othin, the sword of justice symbolising Othin as Lawgiver, and the battle-axe of warfare symbolising Othin as War God.

its door for lack of funds and membership in 1876. In Scotland, the movement was much slower, but the highlanders had abandoned their allegiance to Rome even by 1848. The movement to unite all Christians under a common church was still strong, but they were fighting a losing battle: the 1882 census showed 64% of Niflungans were either full or observing members of the ORW, while only 30% were registered members of the VKN. Johann II himself was not necessarily a believer in either tradition, settling more readily for Enlightenment scepticism. He did, however, know the power the ORW could wield if put in the right position. While Bismarck was alive, there could be no move in this direction, for Johann knew full well he could not outwit the Iron Chancellor, as he had come to be called. Instead, he waited until 1900 to announce that the Orden der Ritter des Wotansauge would begin receiving state funds upon his application for membership, ushering in what he called “a new age of renewed faith in the old ways”. The ORW was suspicious of the highly liberal young king, but were happy to finally receive the recognition heretofore reserved by conservative Christian rulers.

Franz Josef was infuriated with open heathenry in his largest vassal and demanded a renunciation of the ORW, declaring, anachronistically, a crusade against the capital of the ORW in Fichtelberg, Franconia, slightly north-east of Bayreuth. This followed on the heels of the First Vatican Council, convoked in 1868 by Pope Pius IX, ushering in a new age of conservatism in the Roman Catholic Church. Pius IX recognised the Crusade and invited other Christian rulers to join. The call largely fell on deaf ears, since the idea of an actual armed crusade hardly appealed to even the most devout Catholic rulers in 1900, but the papal recognition nevertheless encouraged Johann to back down from his political manoeuvre, and in exchange for ending the crusade promised political recognition of the VKN as well, causing a surge in membership of that body. The ORW maintained its numbers, however, and the surge proved short-lived as more and more people abandoned the Christian churches, where they found a lack of real belief or morality, in favour of the ultra-conservative, nationalistic, and heavily ritualistic ORW. 1902 marked a high point in ORW power, when they announced a week-long Sigrblót festival beginning on May Day and held in every major city in Niflunga. Edinburgh and Glasgow were the only two major cities which saw little celebration of the festival, which culminated in a torch-light march through the streets on the night of 8 May, which concluded with the meeting at a constructed shrine grove outside of each city where verses of the Hávamál were read and the Nine Sacred Degrees of the Order were ritually reinstated with the elevation of a new Grand Master and Ninth Degree Knights of the Order.

Johann, despite being a member in name, largely ignored the celebrations and on the first of May was conspicuously on a diplomatic visit to the Vatican. The new Grand Master of the ORW, however, was Johann's son Karl Wilhelm, who had accepted the title at his father's orders, unbeknownst to the ORW, who saw in him the solid supporter that his father was not. In public, the father and son feigned dislike for one another, the elder in a position to please the emperor, while guaranteeing his dynasty by maintaining his son's popularity with the people. As more and more power was given away to the National Parliament in Edinburgh, the actual role of the king was more a matter of popularity anyway. Johann announced the “Dawn of the New Age” in a speech given before the people in Edinburgh, declaring that the time had come for an age of popular sovereignty and the shattering of old bonds on trade, freedom of expression, and civic participation, opening massive popular elections on the first day of the next year.

Ragnarök[]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Things continued in this way as Niflunga's economy fluctuated violently as a result of the new liberal measures and many of the people, heavily influenced by the ORW, regarded with disgust the massive decline in family life and moral consistency in the elected politicians as well as society as a whole. Unrest was surging throughout the rest of the Empire as well, and in 1914 the conservative Emperor was killed by a bomb in Sarajevo, on his visit to all the major cities of the Empire, that was to take all year. The murder created chaos in the Empire, as liberal Archduke Franz Ferdinand came to power to almost immediately be couped by his nephew Karl Franz, who assumed the name Karl VIII, declaring a continuity with the Holy Roman Emperor Karl VII of the 1740s. He received the blessing of the Pope for his coronation and declared as his first act the reinstatement of the Imperial Electors and the Roman Empire. He became hugely popular among conservative circles in Niflunga, both Christian and Ásatru for this motion, and immediately the enemy of every liberal power on the continent. He blamed socialists for his great-uncle's death, and moved for punishment by banishing all communists, socialists, and similar groups from the German Empire. This led to strong opposition internationally from left-wing nations including Italy, Spain, England, and several small French states. In late 1914 he signed an agreement with Czar Nicholas to curb liberalism and socialism in favour of conservative autocracy, known as the Treaty of the Crowns. His competition with England's navy came to a head soon thereafter, and for reasons which to this day remain unclear, war was declared by the Parisian Communards and their French allies on the German Empire, which was followed by the declaration of alliance between the Dutch and Flemish and the French League; when German troops marched on Holland and Wallonia, England declared war, opening the Great War that would rage for the next four years.

The war went quite well for the German Empire until American involvement in 1916 began to break down supplies and trade, assisting the English embargo against Karl's Empire. The French, however, quickly succumbed to the German advance, and by Christmas 1916, the Habsburg Netherlands were once again a province of the new Holy Roman Empire. Paris was put under siege, but a massive trench line prevented further advance as American and English troops flooded into the French territories. Despite massive military victories, however, liberal dissent at home was growing and the Anglo-American blockade severely hurt supplies and morale at home. By 1918, the Germans were pushed completely out of the Low Countries, and were left without their only ally after Russia fell into revolutionary chaos in 1917. Various non-German nations rose in revolt as well, as the Croats, Hungarians, Serbs, Bosnians, Slovaks, and Czechs revolted against Karl's harsh rule. That same year, the short-lived rebirth of the Holy Roman Empire collapsed as Johann II declared a separate peace with the English, essentially tearing the German constitution to shreds and encouraging the revolt of all non-German ethnicities, which divided the map of Europe into even smaller segments. The peace treaties signed after the war were quite varied; some very harsh, some lenient, some being mere formalities. It was not long after the collapse of the Empire and the declaration of Ragnarök by the ORW that Johann found himself in trouble.

The Rise of the NRP[]

The Nibelungische Reichspartei was formed before the outbreak of the Great War in response to Liberal measures being undertaken by Johann II, founded by the Master of the ORW in Öland. The man's name has been lost to history, but his assumed name as a member of the ORW survives with great honour: Sigurð Angatýrsson. Angatýrsson is believed to have come from Sweden, and spoke both the Norse language as well as German, in which he spoke most fluently and powerfully. His movement was a strong anti-liberal, anti-communist, anti-socialist party associated with both the ORW and the Emperor, drawing support from all corners of Niflunga's conservative circles. The programme of the party was laid out in 1910, two years after its foundation, specifically aimed at folk-nationalism, imperial power, aristocratic rule, and economic autarky. This meant a suspension of parliamentary bodies and the concentration of power in a council of men centred initially around a new King, but after the war this changed to simply an elevated dictator.

A right-wing revolutionary armed with an MP19 keeps guard in one of the war-torn streets of Berlin.

For the duration of the war, Angatýrsson and his supporters found themselves in and out of prison for disruption and sedition. Over the four years, seventeen members of the NRP were sent to the gallows, and more than two hundred were imprisoned. Public sentiment, however, began to turn in favour of the small revolutionary party as things began to turn against the Empire in the war, and after the utter collapse of the Empire at the end of the war, the ORW declared the Ragnarök was upon the world, as cities were devoured in flames of revolution. During the chaos, the Kingdom of Niflunga lost control of the German and Swedish lands, which united under the power of Angatýrsson, who was freed from Spandau prison awaiting his death by the revolutionaries. He quickly found himself in a situation of immense influence; while he appealed to the rabble with powerful speeches and massive rallies held in cooperation with the ORW, he disdained the masses, favouring the rule of the ORW, or an aristocratic structure resembling the Order, over the people who were unable to rule themselves. His personal attitudes and erudition gained from years of reading both before and during his prison sentences appealed to one young Hanoverian who had moved to Bayreuth in the late stages of the Great War. The young philosopher was of strong aristocratic bent of mind, a proponent of a pessimistic interpretation of the future, a massive decline in social life and structures. He was close friends with a certain professor whom he had met in Hamburg and with whom he kept in close contact after the latter's move to Munich. Unlike Angatýrsson, this young philosopher's name was well known in the early days of the movement, but has since disappeared from records in favour of his assumed name upon being elevated to the ninth degree of the ORW, Sigurð Óðinnsson.

Óðinnsson was largely responsible, working closely with Angatýrsson, in formulating the NRP's programme and philosophy. After the collapse of the empire, both men worked to recruit members of the newly formed Freikorps that littered all of Germany, formed of former Imperial Corps of soldiers now without leadership or a united government to follow, roaming the country leaving dead communists and, sadly, unfortunate victims of circumstance in their wake. Only three months after his escape from prison, Angatýrsson had united every Freikorps in Niflunga under his command, an army fully half the size of the Niflungan force that had fought on the Western Front. With them, he declared a new constitution for the Commonwealth of Niflungland (Gemeinwesen Niflungland), now having a fully armed and organised army and a small, but capable navy.

Sigurð Óðinnsson, most recent Vísir of Niflungland, was an instrumental figure in the early government of Angatýrsson after the overthrow of the monarchy.

Angatýrsson himself adopted the title from Old Norse Vísir, or “Leader”. The Niflungan Revolution soon transformed into the Niflungan Civil War, as John III of Scotland raised an army to take back his German and Swedish lands and landed in Pomerania only fifteen days after the declaration of Angatýrsson's constitution. He was defeated and captured at the Battle of Lindow at the hands of his son Karl Wilhelm; his last communication with the parliament in Scotland was to illegitimate Karl Wilhelm as his heir, thus making his nephew Malcolm, Duke of Argyll, heir apparent to the throne, which he assumed upon his father's abdication in prison that very month.

Angatýrsson, however, was quite intent that the old monarchy had become base and decrepit, and the time of the old Kings was over, in favour of a new aristocracy and a new order in Niflunga. While Malcolm VI of Scotland (Malcolm II of Niflunga as a pretender) rallied more troops to attempt to take back Öland before a landing on German soil, Angatýrsson prepared his own landing. Using personal connexions in Flanders, he had readied a massive fleet in Ghent; he had negotiated with Öland to allow for a landing there, where he knew Malcolm would strike to give himself a base of operations in the Baltic. Malcolm was unaware of the movements in Flanders and Holland, now united in a single United Netherlands after the collapse of Habsburg power there. On May Day, there was a massive parade in the standing capital of Niflungland in Leipzig, at which Óðinnsson gave a speech detailing the NRP's internal plans for Niflungland, and Angatýrsson and his troops departed from Ghent.

The Reichsarmee of Niflungland under Angatýrsson's command landed at Irvine in the early morning hours of May 2. A force almost 200,000 strong made its way to Glasgow, catching the garrison there completely off-guard, subduing the city completely by that night. The news of the capture of Glasgow came to Malcom VI as he had just landed on the island of Öland and was engaged in battle with the Swedes there. Angatýrsson was quick to gather all members of the ORW in Scotland to his side, when he announced outside of the City Chambers that Niflungland would once again be complete. News reached the Highlanders of Aberdeen and the Hebrides as well as the Norse Scots of the Orkney and Shetland Islands, who rose in revolt against the rule of Malcolm. By May 22, Edinburgh was under siege from the north and the south-west. The modest forces left loyal to Malcolm quickly fell to the superior numbers of both Scots and Germans loyal to the new government. On that day, Angatýrsson addressed all of Niflungland and the National Parliament in Edinburgh, declaring victory over Malcolm Moray, who went into immediate exile. His father, John, was released from prison but stripped of his honours, ranks, and titles, and forced to live the rest of his life as a private citizen under the name John Murray in Inverness.

Vísir Angatýrsson[]

Angatýrsson as Vísir of Niflungland ushered in a new era for the nation, an era of self-determinism, isolationism, and economic stabilisation. The first act of the new Vísir upon the closure of the Niflungan Civil War that had raged for the past three years was the establishment of defined capitals for the Commonwealth. He knew that to move all government to Germany would likely throw the Scots into revolt, but he could not risk betraying his own movement by keeping the seat of government in Edinburgh. Instead, he looked to the effective rule of South Africa, in which each of the major provinces was given a capital to smooth differences over where the capital should be. He established Edinburgh as the central legislative capital, where the National Parliament had traditionally met, and established the judicial capital where the Hochgericht, administered by the ORW, held court in Leipzig. For the executive branch, it was determined that since all executive power was not merely held but manifested in the person of the Vísir, wherever he kept residence would be the executive capital of Niflungland.

Angatýrsson established his executive capital in the mountains of Franconia, in the festival town of his favourite composer, Bayreuth. After conversations with the Wagner family for two years, he finally convinced Siegfried Wagner to convert his father's home into a national museum. His own home was built not far away, a quaint but nevertheless massive building which could be used for government meetings but was also a simple and sufficient home for the Vísir. During his rule, the effective law-making capability of the legislative body was curbed significantly in favour of a joint domination of government by the Vísir and the High Court of the ORW. Karl Wilhelm remained Grand Master of the ORW, taking a German form of his name von Mörre, and was allowed to maintain his title as Grand Duke of Brandenburg, Saxony, and Pomerania, Duke of Öland, Rothesay, and Argyll, Margrave of Thuringia, etc. He and Angatýrsson worked very closely together on building the New Aristocracy of Niflungland, centred on the ORW. The VKN lost government funding, but survived on the generous donations of old Christian families. By the sixth year of Angatýrsson's rule, it had shrunk to a paltry 19 per cent of the population against 79 per cent who were members of some branch of the ORW. The remaining 2% were either Roman Catholic or non-believers, a segment of the population which Vísir Angatýrsson, Großmeister Karl Wilhelm, and Hochbischoff Günther von Lütwitz all attempted either to eliminate or convert, with some success.

Under Angatýrsson's leadership, Niflungland saw a religious resurgence that the Vísir matched with building projects throughout the Commonwealth, including a massive temple complex in the centre of Berlin in the Tiergarten, comprised, as was traditional, of massive groves of trees and huge stone and marble structures made to resemble Germanic long-houses with a slight classical influence. For his part, however, Angatýrsson rarely left Bayreuth, but nevertheless was active in public life by regularly hosting, in conjunction with the Wagner family to whom he had grown close, the annual Bayreuth Festivals. It was under Angatýrsson's leadership that Niflungland earned its reputation as a centre for artists and the arts. He also saw to it that the old castles of the Scottish lordly families be restored to their former glory, as well as actively encouraging the clan structure of the Highlands, which left the Scots well-pleased with his rule. So well pleased, in fact, that by the eighth year of his rule the House of Commons in the Niflungan Parliament had been completely dissolved, shrinking the governing body even more to just the House of Lords.

After an effective and prosperous ten-year rule of his newly-created commonwealth, the ageing Angatýrsson took severely ill and went to his grave in the dead of winter, leaving the control of Niflungland in the hands of his chief deputy, the young philosopher of the Niflungland Reichspartei, Sigurð Óðinnsson.